Editor – Mugilganesh RM

On October 9, 2023, Claudia Goldin, a Harvard University professor and economic historian, became the third woman to win the Nobel Prize in Economics for her research on women at work. She is the third woman to win this prestigious prize.

Goldin looked back over two hundred years of US labour force data, concentrating on the labour force participation of men and women and the factors contributing to wage disparity between men and women. Her goal was to explain why the pay gap between men and women refuses to close even though many women are better educated than men in high-income countries. Let’s delve into her work to gain an understanding of her findings and subsequently explore its relevance in the Indian context.

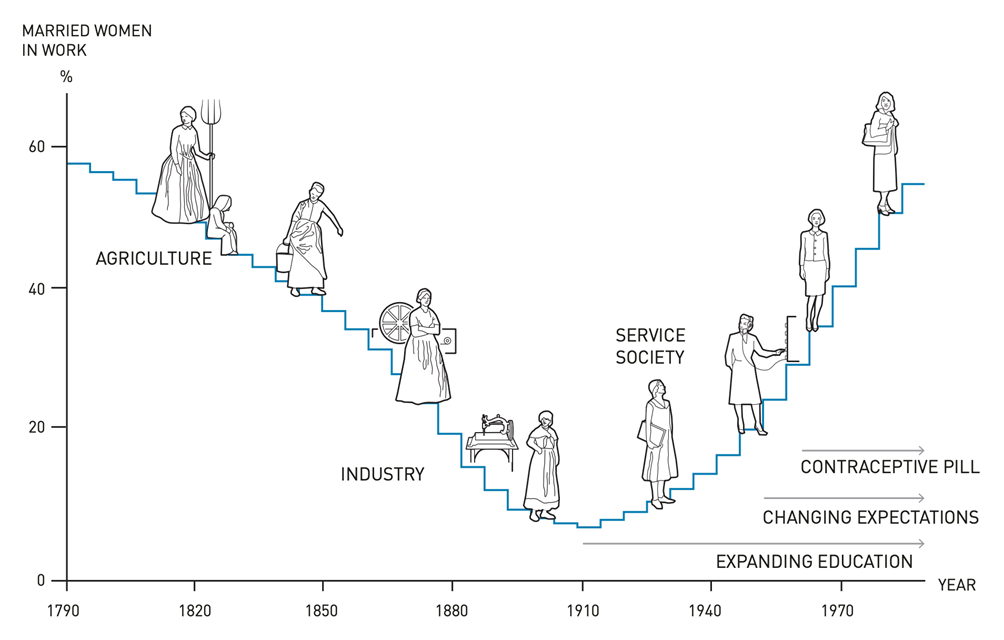

Over the years, researchers predominantly focused on analysing data from the twentieth century, leading to the conclusion that a clear positive association existed between economic growth and the number of women in paid employment. In other words, researchers believed that as the economy grew, more women were in work. However, Goldin’s exploration went beyond this twentieth-century dataset, providing a more comprehensive understanding by uncovering crucial factors that earlier studies had overlooked.

Goldin found that historically when women got married, census records and public documents often categorised their occupation as “wife.” These records indicated that married women were solely engaged in domestic work and did not partake in any paid employment. Contradictory to this data, It was very common for women to work alongside their husbands in agriculture or various forms of family business. Women also worked in cottage industries or production in the home, such as with textiles or dairy goods, but their work was not always registered correctly in the historical record.

Goldin used historical time-use surveys and industrial statistics to correct this data and her corrections revealed that before the rise of industrialisation in the nineteenth century, women were more likely to participate in the labour force. One reason for this reduction in the participation of women during industrialisation was that industrialisation made it harder for many married women to engage in work from their homes and balance both work and family responsibilities.

Goldin showed that women’s historical participation in the US labour force could be described using a U-shaped curve for the two-hundred-year period from the end of the eighteenth century, (i.e) Women’s participation in the labour force declined with the growth of industrialisation and with the advent of more service-oriented jobs women’s participation increased in the labour force. Because economic growth was steady throughout this entire period, Goldin’s curve demonstrated that there is no historically consistent association between women’s participation in the labour market and economic growth.

Goldin also noticed that when the U-curve turned upwards (i.e.) when the participation of women was growing with the growth in the economy, there was a significant difference in the employment rates of married and unmarried women. While around twenty per cent of all women worked for pay, only five per cent of married women did so. Goldin pointed out that legislation known as “marriage bars” often prevented married women from continuing their employment as teachers or office workers, but this wasn’t the only factor.

Goldin also demonstrated that there was another important factor behind the difference between the employment rates of married and unmarried women, which is the “Women’s expectation for their future careers”. In the early twentieth century, most women were only expected to work for a few years before marriage and then to exit the labour market upon marriage, so women who grew up at that time made educational choices based on this conception. However, the latter half of the 20th century witnessed significant societal shifts, making it increasingly viable for married women to reenter the workforce once their children were older. Unfortunately, the job opportunities available during this period did not align with the educational choices made by women who had not anticipated working after marriage. This mismatch in job requirements and women’s educational qualifications exacerbated the existing gender gap. It was only in the subsequent generation that women realised they could pursue lengthy careers even after getting married. As a result, younger women during that period placed a greater emphasis on investing in their education. A ‘quiet revolution’ was beginning.

And then came something else that helped to boost female labour participation rates even further — the contraceptive or birth control pill. Goldin found that the pill gave women more control over their bodies, thus delaying marriage and childbirth. This also helped them make other career choices, and an increasing proportion of women started to study economics, law and medicine. In other words, the pill meant that women could better plan their future and thus also be clearer about what they expected, giving them entirely new incentives to invest in their education and careers.

However, a crucial question remains: why does the gender pay gap continue to persist? If everyone knows the history, shouldn’t it have disappeared by now? Well, the thing is that these days the pay is similar straight out of college. But it begins to diverge once women have families.

Goldin showed that with the introduction of modern pay systems, employers tended to favour employees with long and uninterrupted careers. An article from 2010 demonstrated that initial earnings differences are small. However, a significant shift occurs with the arrival of the first child. Earnings for women, even those with equivalent education and professional backgrounds as men, immediately decline and fail to rebound at the same rate. The key factor contributing to this phenomenon is that when families start, women typically take up the majority of childcare responsibilities. Consequently, they find it challenging to allocate time to demanding work, leading to substantial penalties if they reduce their working hours. This situation contributes to the persistent gender pay gap.

Now, you might ask, why not distribute family duties equally? Economist Claudia Goldin suggests a potential issue with this approach. When children enter the picture, there arises a need for someone to be “on-call” at home, available for emergencies, requiring a flexible schedule or a less demanding job. However, if responsibilities are evenly split, both parents end up sharing the on-call duty, compelling them to opt for less demanding jobs for flexibility. This dual compromise further dampens household earnings. In Goldin’s words, “the 50–50 couple might be happier, but would be poorer.”

While all these findings are focused on the US, let’s try to relate them to the Indian context. The U-curve that Goldin observed in the US can also be observed in India, not through economic development but through the lens of family income. In very poor households, women cannot afford not to work. Hence, the workforce participation rate is high. As family income rises, the women pull back and tend to focus on household work and childcare. With rising incomes, child care and hiring a person to look after the household chores become more affordable, resulting in a higher workforce participation rate.

While the family income factor presents a U-shaped curve from the supply side front, there is also another factor, education, that presents a U-shaped curve from the demand front. Women who are illiterate or have only elementary education, participate more. With secondary education (middle school), their participation rate drops. And with higher education (graduation and post-graduation) their participation picks up again. This is due to the reason that there aren’t adequate and appropriate jobs for women with high school or middle school education. In the absence of jobs, they drop out of the labour force.

In India, even though there has been a rapid shift towards a service sector-oriented economy and the education gap between men and women has reduced, the gender employment gap still persists. The Economic Survey of India 2023, puts the Female Labour Force Participation Ratio (FLFPR) at 27.7%, which means only 27.7% of working-age women are either employed in paid work or are looking for a job. In contrast, countries with very large service sectors have a high FLFPR. The FLFPR in India has been falling steadily for over two decades, although there has been some uptick recently.

So what can be done in India to bring in more women to the workforce? The solution is to avoid the U-curve in both labour supply and demand, the key lies in averting the decrease in workforce participation. This involves addressing institutional and societal factors that contribute to the gender gap in employment, making entry into the workforce more accessible, secure, lucrative, and professionally fulfilling for women. Additionally, fostering support from families and communities is integral to these efforts.

First, Indian women are unable to join the formal workforce because they are occupied from dawn to dusk taking care of the needy ones at home and with household chores. Developing a care economy to cater to the young, the ailing, and the elderly can be transformational or even providing appliances like washing machines that reduce their household workload could also help. This not only has the potential to generate a large number of direct employment across genders but will also free up women to join the formal workforce.

Second, evidence from the East Asian economies shows that women need mobility to be independent, productive, and employment-ready. Providing women with free bus and metro passes, cycles and incentives to own and operate their vehicles could tremendously boost their participation in the labour force.

Third, we must make our cities and workplaces safer. Safety is one of the primary reasons for the low engagement of women in paid work in India. Making our cities safer would require a lot of awareness and educational programs, presence of women mass in public spaces, and the deployment of more women as security staff, in the police force, and transportation sector.

Working women often need affordable and safe housing in urban and semi-urban areas. Gender-based discrimination against single women in renting homes must be addressed. Additionally, devising programs to help women in their 30s and 40s to re-enter the workforce after the bulk of their childcare responsibilities are over, inculcation of gender-neutral behaviour among boys and girls from a young age, giving women more access to information can also significantly contribute in increasing the participation of women in the workforce.

Finally, we need to bridge the leadership gaps in all spheres of public life. The recent legislation for women’s quota in Parliament and state assemblies is a welcome move. Across most states, 50 per cent of all elected persons in village, town and city councils and corporations are women, thanks to reservations in the third tier of government. But what is off-putting is that a large number of glass ceilings remain intact even after 75 years of Independence. Out of the 25 individuals who have held the position of RBI governor to date, none have been women. Similarly, among the 64 deputy RBI governors, only three are women. Furthermore, none of the 18 Chief Economic Advisors in India’s history has been a woman. There has never been a woman Vice Chairperson of NITI Aayog or its predecessor, the Planning Commission. Additionally, there has never been a woman member of NITI Aayog, a woman Chief Justice of India, a woman head of the Finance Commission, or a full-time woman Chief Election Commissioner. This list could go on.

If we could eliminate the gap between men and women, or at least narrow down the gap, India’s GDP could show a significant jump. Thanks to Goldin’s prize, these issues have come into sharp focus.

What’s your take? Can India surmount the social and institutional barriers impacting female labour force participation? Share your thoughts in the comments or drop in a mail to tjef.tapmi@manipal.edu. We will be happy to read them.

References:

Leave a comment