–Junior Editor

– Sowmika Konduru

When analysing the recent growth achievements of many nations, particularly India, the argument that the wealthy are growing richer and the poor are getting poorer is frequently cited. Empirical research supports the general belief in India that the advantages of higher GDP development are being eroded by its pro-rich bias. In other words, development has not led to the country’s reduction in inequality or the creation of lucrative jobs. At least in India, the issue of jobless growth is not new.

The top quintile’s average per capita income in 2013–2014 was over 11 times higher than that of the bottom quintile. According to the findings of a recent survey, 85% of the bottom-segment households are located in rural India, while roughly 63% of the top 10% of wealthy Indians live in urban areas. A little over 14% of the GDP is generated by agriculture, which is the primary source of income for more than half of Indian families.

Additionally, the majority of wealthy Indians reside in areas with the highest levels of urbanisation, which compounds spatial inequities. In addition, young people from rural regions who don’t want to work on farms are rapidly moving to urban edge and semi-urban areas in search of non-farm jobs. The intimidating and growing requests for reservations for their communities in educational institutions and public sector jobs made by the Patels and Jats, respectively, in two rich Indian states—Gujarat and Haryana—reflect the failure of the current growth model to accommodate the million or so young Indians who enter the labour force each month. In reality, it is a reflection of the insufficient job creation that causes social movements to call for preferential treatment and protection, with the ensuing social and economic repercussions, including a decline in trust in institutions.

Achieving economic growth is one of the fundamental objectives of macroeconomic policy. All government policies are therefore created to be compatible with the government’s goal of economic growth. But why is the government so interested in economic expansion? This has several possible answers, but gaining political popularity is the most crucial one. The pattern is as follows: when there is an increase in output, employment will increase, and the decline in unemployment boosts public support for the government, thereby helping it win elections. In order to win the public’s support for reelection, the government will thus continually endeavour to increase output even at the expense of inflation. Does increasing output always result in more employment is the key query for this episode.

This article seeks to comprehend the causes of the fall in job creation as well as to offer potential government policy solutions to make sure there are enough jobs being generated in the economy.

JOBLESS GROWTH

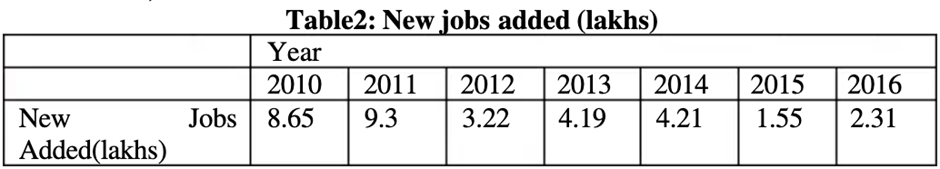

The phrase “jobless growth” refers to a circumstance in which the nation’s GDP increases but the amount of new jobs created declines or stagnates. The following tables represent the data by the World bank on India’s GDP growth, and new jobs added from 2010-2016.

As can be seen, the number of new jobs created has declined from 8.89 lakhs in 2009 to 2.31 lakhs in 2016. In the same time frame, employment elasticity decreased from 0.3% (1991-2007) to 0.15% in the present. Employment elasticity is the indicator of the percentage shift in employment that corresponds to a 1% change in economic growth.

WHAT CAUSES JOBLESS GROWTH?

If we use the GDP as a measurement, the economy is performing reasonably well. The increased employment prospects for those who are a natural corollary of economic progress and wealth, however, does not occur concurrently. Job losses due to automation, consolidation, rightsizing, and technical advancements further exacerbate the lack of employment possibilities. Consolidation in the BFSI, IT, and telecom industries resulted in the loss of up to 1.5 million jobs in India between 2016 and 2017 (Madhavan, 2018). Furthermore, in the IT industry, it only took 16,055 personnel in 2015–16 compared to 31,846 in 2009–10 to provide $1 billion in exports (Madhavan, 2018). It indicates that job losses significantly contribute to the rise in the number of unemployed people.

The lack of jobs is a result of the interaction between two surpluses: excess capital and excess labour. In order to solve the issues of high salaries in wealthy nations and antiquated labour rules in underdeveloped countries, excess money is typically invested in labour-saving technology and automation. Robots are being used as workforce replacements by businesses across India. For instance, Honda scooter facility in Vithalapur has big robots in their shop floor lowering the number of humans down to 14 from previously 72, while Suzuki Motors India Ltd. is utilising 5000 robots at its Manesar and Gurugram facilities(Raj, 2017).

According to a World Bank study from 2016, 69% of Indian employment might be eliminated by technology(World Bank, 2016). In addition to automation and robotization, a significant factor in the rise in the number of unemployed people is the unwillingness of business entities to hire workers as a result of India’s strict labour regulations. Policy paralysis in regards to labour reforms has prevented the country from benefiting from demographic dividend; sporadic changes to labour laws have not been able to draw in foreign investors or encourage domestic business owners to expand their manufacturing capacities(Jha, 2014). If the government implements the required reforms to the labour laws while balancing the interests of employees and companies, employment prospects can be opened beyond all expectations.

EMPLOYMENT CONDITIONS AND DISTRIBUTION OF WORKERS

According to the NSS survey findings for the 61st and 66th rounds in 2004-05 and 2009-10, respectively, a sizable number of workers in both rural and urban parts of the nation lack formal written employment contracts and are ineligible for paid vacation. From the 61st to the 66th round of the NSSO survey, the proportion of women in such work circumstances in rural areas slightly decreased from 69.6% to 65.3%, whereas the proportion of men climbed from 71.5 to 77.1%. Urban regions exhibit a similar trend as well; there, the percentage of men without a signed employment contract rose from 54.8 to 56.7%.

The findings demonstrate that a significant fraction of Indian employees participate in informal employment in the unorganised sector, where they are not eligible for the same basic social security benefits as their counterparts in the formal and organised sectors. The inapplicability of the majority of labour laws to the informal sector and the gaps in the distribution of benefits that the informal labourers have a right to under the different initiatives introduced by the central and state governments for workers’ welfare are two of the main contributors to the gap in working conditions between the formal and informal sectors. These issues are primarily attributable to shortcomings in data collection and the absence of transparency of those who operate the informal space.

Trends in distribution of workers in formal and informal sectors The informal sector of India accounts for more than 90% of all employment (defined as those lacking social insurance), and it also accounts for approximately 85% of employment in non-agricultural sectors. Despite the fact that India is one of the biggest and most rapidly expanding economies in the world, informality has always been a serious issue. The stickiness of this statistic continues to be a serious area of worry, according to a 2019 International Labour Organisation (ILO) the numbers entering the labour force will only increase over the next ten years until 2030 (from which the growth in the labour force is expected to decelerate). After the early 1980s, India has benefited from a demographic dividend; however, it will stop by 2040.

The overall quality of jobs also needs to increase, in conjunction with the skill level of the workforce, in order for them to be able to adjust to the swiftly industrialising job markets and the steady integration of advancements in technological expertise to propel economic growth, which is clearly a policy imperative. This is in addition to the non-agricultural jobs growing at a pace at least in accordance with the growth in the labour force. This will prevent structural unemployment, which has negative effects on the employees’ income and general quality of life, from affecting those working in occupations that are more likely to be automated in the near future.

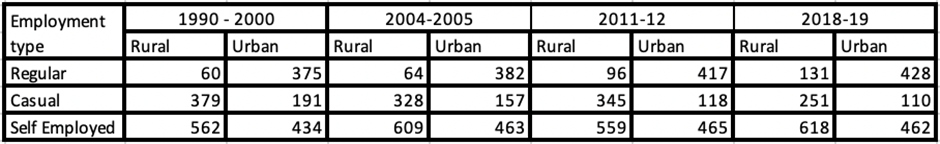

Data on the distribution of employees by household type from 1999–2000 to 2018–19 are shown in the table above. For all years, urban regions have a larger proportion of households with the household type “regular,” but rural areas have a higher proportion of families with the household type “casual.” The biggest percentage of families are self-employed, and this percentage has risen over time. In rural areas, the number of families classified as “self-employed” climbed from 562 to 618 per thousand between 1999-2000 and 2018-19, while it increased from 434 to 462 per thousand in urban areas. ‘Regular’ households have grown over time as well, rising from 375 to 428 in urban areas and from 60 to 131 in rural regions (between 1999-2000 and 2018-19).

Only the number of ‘casual’ homes has decreased over the years, and this applies for rural as well as urban areas. The proportion of “casual” households fell from 379 to 251 per thousand in rural areas and from 191 to 110 per thousand in urban areas between 1999-2000 and 2018-19. In general, both independent contractors and temporary employees belong to the unorganised labour market, which has no advantages or job security. Thus, despite initiatives like MGNREGA, the prevalence of informal labourers is substantially greater in rural than in urban areas (86.9% against 57.2%).

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN GROWTH AND EMPLOYMENT DISCONNECT

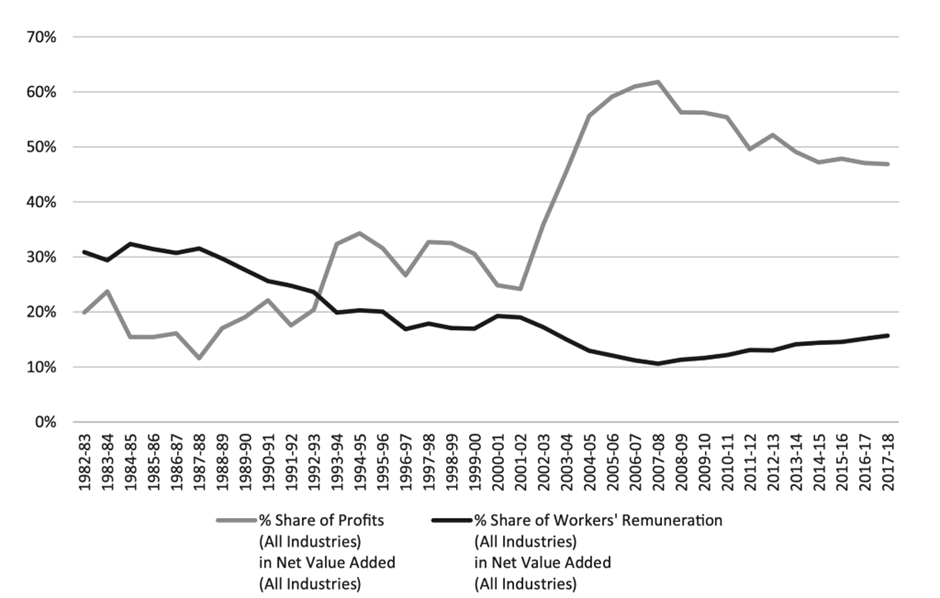

India’s structural change deviates from tradition. The phase of industrialisation where a nation experiences manufacturing-driven, employment-intensive growth has been skipped in favour of services-driven prosperity. Although the services sector made a significant contribution to growth over the past ten years, its employment share (25%) is significantly lower than its GDP share. Therefore, from the standpoint of inclusion, India’s sectoral composition of growth has fallen short in that it has produced significantly fewer chances for the country’s poor to find lucrative jobs. In the 30 years since 1983, the percentage of salaries in net value generated by industries has shown a secular fall, while the share of profits has increased (see Figure 1).

Increased informality and contractual employment of the labour force is an unintended outcome of labour laws that are meant to safeguard employees but really cause harm to them. In the private organised sector, there were two out of every three unorganised workers who did not have access to social security in 2011–2012. It is not surprising that India’s recent growth trajectory has been characterised as “jobless” given the rising capital intensity of manufacturing (Figure 1) and the country’s economic development. In actuality, inequality has increased since the early 1990s.

India has substantial difficulty as a result of the employment dilemma that exists in the background of the ongoing structural change, which hurts both the industrial and services sectors of the Indian economy. This necessitates a review of the factors that contribute to low employment growth rates in spite of strong economic development and favourable demographics. To achieve the main goal of the “Make in India” plan, India must unquestionably increase manufacturing growth in order to hire more employees. In order to make manufacturing a jobs-escalator for India, several acknowledged obstacles—infrastructure delays, land acquisition, and environmental clearances—need to be resolved along with a relaxation of labour laws.

Recently, the economy’s startup sector has shown unprecedented activity. Multiple strategies at both ends of the spectrum—from informal to formal, from agricultural to manufacturing, from stiff to flexible, from full term to fixed, and from formal to gig—will be required to address growth and jobs.

Figure 1 – Gap between profits and workers’ wages in net value added in industry

THE WAY FORWARD FOR INDIA

India has to develop and execute a thorough national employment policy immediately. Here are a few recommendations:

- Factor market reform: The only completely unreformed components of the Indian market are land and labour. Land market changes will boost the supply of available land, while labour reforms that loosen up employment contracts will raise the desire of employers to hire labour.

- Provide states, cities, and local organisations at the district and village levels additional authority: The role of the centre is to establish favourable macroeconomic circumstances that will promote increased economic activity. However, measures to promote job creation can be most effective at the state, city, and district levels. This is true whether it comes to enhancing labour market information systems, skill development, or putting into place changes to factor markets that promote job creation.

- Rebalance tax policy: Tax policies need to reverse their tendency to favour capital-based incomes over wage incomes. This will inevitably reduce the appeal of excessive capital utilisation and automation in a labour-surplus economy without necessarily having an influence on the adoption of new technologies to boost productivity.

- Creating a more flexible educational and skilling ecosystem: Policies must place a strong priority on the establishment of new educational and skilling institutions that can swiftly convert changing skill-demand patterns into courses and certificates that are helpful to both job seekers and recruiters.

- Substitute universal (or even tailored) income support schemes for the existing physical subsidy system: It is necessary to convert practically all subsidies to a cash-based system using the direct benefits transfer approach. This will open up real new markets for goods like food, fertiliser, and gasoline, among other things, and it will also give workers greater freedom to move around.

- Focus on industries that can create jobs quickly: Aside from app-based services, industries like construction, real estate, logistics, transport, clothing and leather products, furniture, education, and healthcare need to receive the most assistance possible with the least amount of regulatory friction.

- Expanding the apprentice programme and instituting fixed-term employment agreements will solve half of the country’s talent shortage and employment issues. Additionally, the bias towards capital-intensive investment will start to diminish if businesses are allowed by supporting legislation to provide fixed-term contracts combined with transferable social security benefits. There will be millions of businesses that formalise employment agreements and generate jobs.

The government may additionally enhance other factors to increase yields from agriculture, storage spaces. and fair price accruals to farmers in order to increase livelihoods and employment opportunities(Jha, Mohapatra, and Lodha, 2019). This will help to reduce the distress in the farming sector. Additionally, in order to expand employment possibilities in the manufacturing sector, the government must refocus on the “Make in India” project, which was introduced with a great deal of excitement during Narendra Modi’s first term as Prime Minister (Jha, 2015). In addition, the government must increase the ability of banking institutions to lend money more freely in order to counteract the customers’ negative attitudes following India’s economic slump. Increasing demand brought on by increasing consumption will instantly boost the employment market. But given bank capital adequacy requirements and an increase in non-performing assets, that is a little difficult. Nevertheless, as an aspect of public policy, the government can recapitalize the banks to promote general economic progress.

CONCLUSION

India’s economy is growing, but there are still serious obstacles to job development and high-quality education. If the situation of jobless growth that we are presently experiencing continues for subsequent expansion periods, it might significantly jeopardise the social, political, and economic stability of our nation. Even if there are many causes for jobless growth, as we have already shown, if the proper policies are put in place, it can be mitigated and an avenue can be created for sustainable levels of employment growth in the nation. In addition to ensuring a safer workplace for women in the workforce, tackling these concerns demands an emphasis on mass education, high-quality instructors, and circumstances for labour-intensive manufacturing. These remedial actions are crucial if we are to avoid a demographic catastrophe and convert our nation into a developed one in the ensuing decades. Let’s face it, though: India’s jobless growth is a long-term trend.

References

Indus Foundation International Journals UGC Approved. (2017). The case of jobless growth situation in India. Indusfoundation. https://www.academia.edu/35549208/The_Case_of_Jobless_Growth_Situation_in_India

Jha, S., & Mohapatra, A. K. (2019). Jobless growth in India: the way forward. Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3476599

Kannan, K. P. (2022). India’s elusive quest for inclusive development: An employment perspective. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics, 65(3), 579–623. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-022-00393-7

Livemint. (2022, August 3). Letting jobless growth worsen is way too risky | Mint. Mint. https://www.livemint.com/opinion/online-views/letting-jobless-growth-worsen-is-way-too-risky-11659542875886.html

Mehrotra, N. (2023). ‘Jobless growth’ fuels India’s unemployment crisis. New Lines Magazine. https://newlinesmag.com/reportage/jobless-growth-fuels-indias-unemployment-crisis/https://newlinesmag.com/reportage/jobless-growth-fuels-indias-unemployment-crisis/

Sen, S. (2019). Jobless Growth in India during the 12th Five Year Plan (2012-2017). Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3719969

Leave a comment